Apple Store in Shanghai, China.

Paul Souders/Getty Images

Paul Souders/Getty Images

This is Part 4 in our Planet Money newsletter series on manufacturing and America. Part 1 asked why Americans aren’t filling the manufacturing jobs that are already here. Part 2 dived deep into economic research that finds that manufacturing jobs pay a higher premium than many other industries. Part 3 asked whether manufacturing-based economic development could help America’s heartland catch up with its major cities. Subscribe here for the next installment. As always, our podcast is here.

In a narrative that reads like a modern-day economic saga, planeloads of top American engineers make their way to China, imparting skills in advanced manufacturing. This massive investment, surpassing even the Marshall Plan’s scale, has been pivotal in China’s transformation into a manufacturing powerhouse. Apple, once a linchpin in this transformation, finds itself reliant on a nation now considered one of America’s chief rivals.

A new book by Financial Times journalist Patrick McGee, titled Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company, delves into this intricate relationship. Whether seen as a triumph of capitalism lifting a nation out of poverty or as a cautionary tale of economic entanglement with a rising geopolitical power, the book offers a compelling look at how Apple became entwined with China’s rapid ascent.

An Origin Story for Apple’s Entanglement in China

Back in 1999, Terry Gou, leading a then-obscure Taiwanese firm called Foxconn, reached out to Tim Cook, a fresh face at Apple who would later become its CEO. This was a critical juncture for Apple, which was banking on the newly developed iMac to spearhead a comeback after narrowly avoiding bankruptcy two years earlier. The iMac, with its unique teardrop design and vibrant colors, demanded precision manufacturing.

Initially, Apple manufactured domestically, even employing Steve Jobs’ sister for manual assembly in its fledgling days. The Apple II’s popularity saw an informal network of immigrant workers in California handling assembly, often in substandard conditions, a detail chronicled by Michael Malone in Infinite Loop.

However, as financial pressures mounted in the mid-1990s, Apple increasingly outsourced production to cut costs and improve efficiency. By 1999, production was spread across continents, but the iMac’s success tested this strategy. LG, responsible for the monitor’s manufacturing, faced challenges scaling up, prompting Foxconn’s Gou to seize an opportunity to enhance ties with Apple through a direct call to Cook.

This marked the start of a transformative business relationship, not only for Apple and Foxconn but also for China’s economic trajectory and the global balance of power. Foxconn, although based in Taiwan, relied on mainland Chinese factories, a shift driven by rising labor costs in Taiwan during the 1980s.

How Chinese Manufacturing Got Much More Advanced

Foxconn’s evolution paralleled China’s own economic model, particularly in the Guangdong province, where industrial capitalism thrived within special economic zones. These zones, supported by local officials and Taiwanese entrepreneurs, became magnets for migrant workers, transforming the region into a manufacturing hub.

China’s restrictive migration policies were relaxed to channel labor into these zones, creating vast factory communities. Workers endured grueling conditions, often leading to distressing incidents at Foxconn plants. Despite this, McGee emphasizes the appeal of China’s manufacturing capabilities went beyond labor to include responsive government and contractor cooperation, which was crucial for Apple’s demanding standards.

By 2000, Apple’s collaboration with Foxconn deepened. Steve Jobs, initially keen on retaining domestic manufacturing, shifted his perspective amid the tech downturn and China’s entry into the World Trade Organization, which made the country more attractive for business.

Foxconn emerged as a key partner, demonstrating remarkable efficiency, known as ‘China speed,’ that impressed Apple’s engineers. The company’s strategy involved offering low-cost, high-quality production in exchange for valuable insights from Apple’s practices.

McGee notes that by 2009, a decade after the pivotal call between Cook and Gou, Apple’s manufacturing had shifted almost entirely to China, a transition he terms “Chinafication” rather than mere globalization.

The Legacy of Apple In China

McGee’s book presents compelling statistics on Apple’s role in China’s industrial rise. By 2012, Apple’s machinery investments in China exceeded its U.S. assets, reaching $7.3 billion. By 2015, annual investments in China soared to $55 billion, excluding component costs.

Perhaps Apple’s most significant contribution was training China’s workforce in advanced manufacturing techniques. McGee highlights Apple’s efforts to maintain quality by sending engineers to China, fostering innovation that rivals geopolitical events in impact.

This knowledge transfer allowed China to replicate Apple’s model, enticing companies like Tesla and bolstering its own industries to compete globally.

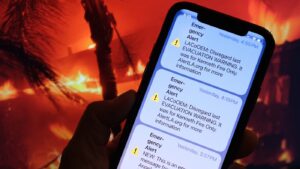

Initially, American political sentiment favored engaging with China, a stance that shifted around 2013 with China’s authoritarian shift under Xi Jinping and growing awareness of free trade’s downsides. This left Apple in a complex position, reliant on Chinese production amid political demands for diversification.

Challenges loom over Apple’s future in China. Can it diversify production to places like India or Mexico? McGee suggests this is daunting due to China’s established supply chains, skilled workforce, and competitive domestic industries.

Postscript: What Apple In China May Teach Us About the Importance of Manufacturing

This article is part of Planet Money’s manufacturing series, exploring the sector’s significance in American politics. Manufacturing proponents argue its importance for national security and innovation, points reinforced by McGee’s narrative.

National security considerations underscore the need for domestic production capabilities, historically vital for defense. McGee’s work suggests tech manufacturing’s offshoring may also impact security, as it enabled China’s rapid development and innovation.

The decline in domestic manufacturing may hinder America’s ability to innovate in physical production, affecting competitiveness in emerging industries crucial for jobs and security.

The series will continue examining these themes. Stay informed by subscribing here.

Be First to Comment